Your toddler has just thrown a tantrum and you are grappling with how to respond: Is it okay to set boundaries by sending them off to their bedroom? As the summer approaches, psychologists and families are still divided over these questions, reviving the debate around constraint or sanction-free education, otherwise known as ‘positive education’.

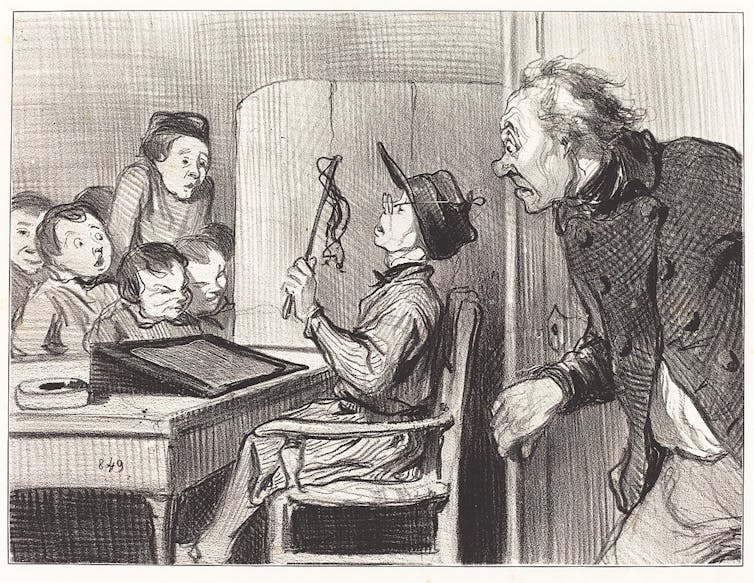

No one would disagree that the educational process should be rid of all physical and psychological violence. The brutality of past centuries is chilling. From the cane to the dunce’s cap to solitary confinement, the range of merciless punitive practices is almost endless, as shown by the recently published Whip and smack dictionary_(i.e. Dictionnaire du fouet et de la fessée)_.

However, banning violence is not the same as condemning authority. Coercion has its virtues, as does punishment. It is astonishing in this debate to see how educational history is often falsified or even simply forgotten.

Constraint-free schools: history of a failed utopia

It should be remembered that a school free of coercion and punishment already existed, through the experience of the Hamburg peer masters, in the 1920s. “From the very first days, the teachers told their pupils that there would be no more punishments or sanctions, indeed, no more talk of prohibitions or of any rules that might hinder them in the use of their full freedom,” writes the Swiss educationalist Jakob Robert Schmid, who recounts this astonishing experience in Le maître-camarade et la pédagogie libertaire (our English translation: The teacher-comrade and the libertarian education).

The Hamburg teachers believed that only freedom, understood as the absence of constraint, could unlock the treasures of childhood.

National Gallery of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia

In its most radical form, this experiment embodied the utopia of an educational space free of all forms of constraint. It ended in a resounding failure, all the more bitter because for more than ten years these innovative masters had shown uncommon enthusiasm. According to Schmid, Kurt Zeidler, one of the movement’s most notorious cheerleaders, had to admit not without sadness that:

Wherever people allowed themselves to be guided by an unbounded confidence in the tact of children, in their strength of will, in their perseverance, in the sureness of their instincts and in the tolerance of individuals to form a community […], we saw gangs of unruly children forming…“.

Let’s make no mistake, therefore: children need to be guided and sometimes coerced. In his New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, Freud makes crystal clear that the first function of education is to teach the child “to control his instincts. It is impossible to give him liberty to carry out all his impulses without restriction’ consequently ‘education must inhibit, forbid and suppress”.

The task of child-rearing calls above all for encouragement, support and appreciation, but it cannot happen without prohibition.

The educational impact of punishment

Proponents of what I like to call the “neither-nor” ideology (neither coercion nor punishment) often refer to educational experiences which, contrary to what they may say, have never prohibited punishment. Opened by Tolstoy in 1859 for a few short years, the school at Iasnaya Poliana is one of such models that did, in fact, resort to exclusion and deprivation.

The Italian doctor and educationalist Maria Montessori is also brought up. Yet her Casa dei Bambini, which brought together very young children, mentions in their 1913 internal rules that “unruly” and “slovenly and dirty” children would be expelled from the school. There were also sanctions at Summerhill, the school founded in 1921 by the Scottish educationalist Alexander Neill, which was intended to be a free place. Fines, warnings and chores were all distributed… by other children set up as a court of law.

Generally speaking, the schools that have claimed to be free of any sanctions are often schools that have welcomed small, or even select, numbers of pupils, thus contravening the principle of hospitality. They are also schools that have hidden their punitive practices behind so-called “natural” sanctions. Finally, they are schools where the adults have rid themselves of the right to punish and bequeathed it to the children, as was the case at Summerhill.

The most innovative perspectives come not from those who have tried to sap the reality of punishment, but rather those who have focused on endowing it with educational meaning. In particular, history shows that an educational sanction always has a threefold purpose: to reaffirm a shared rule, to make a young person who is growing up aware of their responsibilities, and to show them boundaries.

The educational sanction is, by nature, suspensive: it momentarily suspends a right. It narrows, for a moment, the field of possibilities and opportunities: “I’m not going to speak to you again because you’ve been saying unpleasant things all afternoon”; “I’ll stop helping you because you’re not doing what you’re supposed to, you’re not abiding by the contract”.

Let’s stop thinking of punishment as penance – that chapter is closed. Penalties are not there to hurt, but to make sense. They can also, under certain circumstances, take on a restorative form: “You’re always annoying little Paul: you’re now going to show him what it’s like to be a grown-up, and you’re going to help him with his homework until the end of the week”. Repairing is certainly repairing something, but it’s also, and above all, repairing for someone.

The rule, constraint and guarantee of rights

The “neither-nor” ideology is making a comeback with positive education. As Denis Jeffrey, a professor of education at Laval University, Quebec, notes, we start by silencing and renaming. For want of thought, we play with words, the teacher rebranded as a coach or facilitator; the rule, as an expectation, the punishment, as a consequence.

Let’s face it: a teacher teaches, a rule is a rule. Perhaps it’s worth remembering that there are three dimensions to the idea of a rule:

- Rule means regularity. A rule is something that recurs on a regular basis, in the sense that it is predictable;

- Derived from the Latin “regere” (to direct), the rule constrains;

- And last but not least, it guarantees rights. To educate is not to devise stratagems to conceal social rules under supposedly natural constraints, as the French Enlightenment philosopher, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, suggests in Émile. To educate is to move the child from the Greek religious concept of the rule, Thémis, to the legal one, Nomos.

The first conception is always religious. The rule is inevitably perceived by the child as a transcendental and immutable authority. It is experienced as a limit to their plans, and desires. Impressive and intimidating, it encourages, paradoxical as it may seem, play and transgression.

Growing up means opening up to a legal concept that encompasses three very different characteristics. Children understand that they can participate in the construction of the rule. It is true that once a rule has been developed, it acquires a form of transcendence, but this transcendence can be changed, improved or adapted. The rule is experienced less as a limit than as a link. It connects us by demanding the same duties and guaranteeing the same rights. The heart of educational work is precisely to bring every child into this peaceful and intelligent relationship with the rules.![]()

Eirick Prairat, Professeur de Philosophie de l’éducation, membre de l’Institut universitaire de France (IUF), Université de Lorraine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recent Comments