MI PHAM/Unsplash

Christine Nguyen, University of Southern California

In the past two decades, children have become more obese and have developed obesity at a younger age. A 2020 report found that 14.7 million children and adolescents in the U.S. live with obesity.

Because obesity is a known risk factor for serious health problems, its rapid increase during the COVID-19 pandemic raised alarms.

Without intervention, many obese adolescents will remain obese as adults. Even before adulthood, some children will have serious health problems beginning in their preteen years.

To address these issues, in early 2023, the American Academy of Pediatrics released its first new obesity management guidelines in 15 years.

I am a pediatric gastroenterologist who sees children in the largest public hospital in California, and I have witnessed a clear trend over the last two decades. Early in my practice, I only occasionally saw a child with a complication of obesity; now I see multiple referrals each month. Some of these children have severe obesity and several health complications that require multiple specialists.

These observations prompted my reporting for the California Health Equity Fellowship at the University of Southern California.

It’s important to note that not all children who carry extra weight are unhealthy. But evidence supports that obesity, especially severe obesity, requires further assessment.

How obesity is measured

The World Health Organization defines obesity as “abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health.”

Measuring fat composition requires specialized equipment that is not available in a regular doctor’s office. Therefore most clinicians use body measurements to screen for obesity.

One method is body mass index, or BMI, a calculation based on a child’s height and weight compared to age- and sex-matched peers. BMI doesn’t measure body fat, but when BMI is high, it correlates with total body fat.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, a child qualifies as overweight at a BMI between the 85th and 95th percentile. Obese is defined as a BMI above the 95th percentile. Other screens for obesity include waist circumference and skin-fold thickness, but these methods are less common.

Because many children exceeded the limits of existing growth charts, in 2022 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention introduced extended growth charts for severe obesity. Severe obesity occurs when a child reaches the 120th percentile or has a BMI over 35. For instance, a 6-year-old boy who is 48 inches tall and is 110 pounds would meet criteria for severe obesity because his BMI is 139th percentile.

Severe obesity carries a heightened risk of liver disease, cardiovascular disease and metabolic problems such as diabetes. As of 2016, almost 8% of children ages 2 to 19 had severe obesity.

Other health problems associated with severe obesity include obstructive sleep apnea, bone and joint problems that can cause early arthritis, high blood pressure and kidney disease. Many of these problems occur together.

How obesity affects the liver

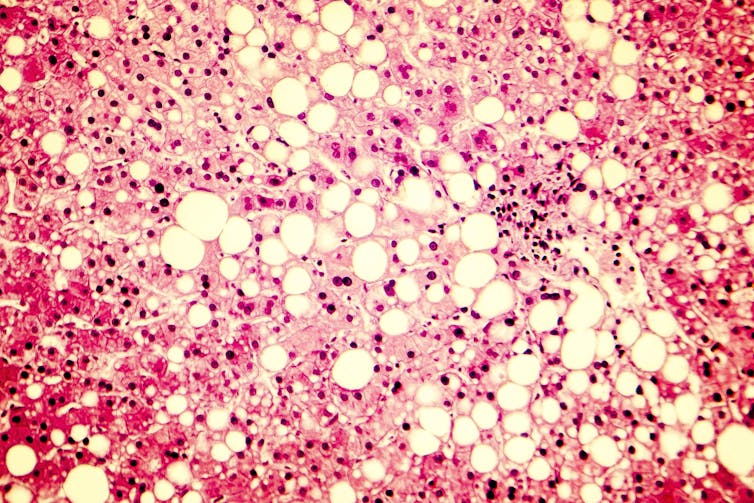

The liver disease associated with obesity is called nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. To store excess dietary fat and sugar, the liver’s cells fill with fat. Excess carbohydrates in particular get processed into substances similar to the breakdown products of alcohols. Under the microscope, a pediatric fatty liver looks similar to a liver with alcohol damage.

Occasionally children with fatty liver are not obese; however, the greatest risk factor for fatty liver is obesity. At the same BMI, Hispanic and Asian children are more susceptible to fatty liver disease than Black and white children. Weight reduction or reducing the consumption of fructose, a naturally occurring sugar and common food additive – even without significant weight loss – improves fatty liver.

Fatty liver is the most common chronic liver disease in children and adults. In Southern California, pediatric fatty liver doubled from 2009 to 2018. The disease can progress rapidly in children, and some will have liver scarring after only a few years.

Although few children currently require liver transplants for fatty liver, it is the most rapidly increasing reason for transplantation in young adults. Fatty liver is the second-most common reason for liver transplantation in the U.S., and it will be the leading cause in the future.

Dr_Microbe/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Links between obesity and diabetes

Fatty liver is implicated in metabolic syndrome, a group of conditions that cluster together and increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

In a telephone interview, Dr. Barry Reiner, a pediatric endocrinologist, voiced his concerns to me about obesity and diabetes.

“When I started my practice, I had never heard of type 2 diabetes in children,” says Reiner. “Now, depending on which part of the U.S., between a quarter and a third of new cases of diabetes are type 2.”

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease previously called juvenile-onset diabetes. Conversely, type 2 diabetes was historically considered an adult disease.

However, type 2 diabetes is increasing in children, and obesity is the major risk factor. While both types of diabetes have genetic and lifestyle influences, type 2 is more modifiable through diet and exercise.

By 2060, the number of people under 20 with type 2 diabetes will increase by 700%. Black, Latino, Asian, Pacific Islander and Native American/Alaska Native children will have more type 2 diabetes diagnoses than white children.

“The seriousness of type 2 diabetes in children is underestimated,” says Reiner. He added that many people express a misconception that type 2 diabetes is a mild, slow-moving disease.

Reiner pointed to an important study showing that type 2 diabetes acquired in childhood can rapidly progress. As early as 10 to 12 years after their childhood diagnosis, patients developed nerve damage, kidney problems and vision damage. By 15 years after diagnosis, at an average age of 27, almost 70% of the patients had high blood pressure.

Most patients had more than one complication. Although rare, a few patients experienced heart attacks and strokes. When people with childhood onset diabetes became pregnant, 24% delivered premature infants, over double the rate in the general population.

Heart health

Cardiovascular changes associated with obesity and severe obesity can also increase a child’s lifetime chance of heart attacks and strokes. Carrying extra weight at 6 to 7 years old can result in higher blood pressure, cholesterol and artery stiffness by 11 to 12 years of age. Obesity changes the structure of the heart, making the muscle thicken and expand.

Although still uncommon, more people in their 20s, 30s and 40s are having strokes and heart attacks than a few decades ago. Although many factors may contribute to heart attack and stroke, obesity adds to that risk.

Talk about being healthy, not focusing on weight

Venus Kalami, a registered dietitian, spoke with me about the environmental and societal influences on childhood obesity.

“Food, diet, lifestyle and weight are often a proxy for something greater going on in someone’s life,” says Kalami.

Factors beyond a child’s control, including depression, access to healthy food and walkable neighborhoods, contribute to obesity.

Parents may wonder how to help children without introducing shame or blame. First, conversations about weight and food should be age appropriate.

“A 6-year-old does not need to be thinking about their weight,” says Kalami. She adds that even preteens and teenagers should not be focusing on their weight, though they likely already are.

Even “good-natured” teasing is harmful. Avoid diet talk, and instead discuss health. Kalami recommends that adults explain how healthy habits can improve mood, focus or kids’ performance in a favorite activity.

“A 12-year-old isn’t always going to know what is healthy,” Kalami said. “Help them pick what’s available and make the best choice, which may not be the perfect choice.”

Any weight talk, either criticism or compliments for weight loss, may backfire, she adds. Praising a child for their weight loss can reinforce a negative cycle of disordered eating. Instead, cheer the child’s better health and good choices.

Dr. Muneeza Mirza, a pediatrician, recommends that parents model healthful behavior.

“Changes should be made for the whole family,” says Mirza. “It shouldn’t be considered a punishment for that kid.”![]()

Christine Nguyen, 2023 California Health Equity Fellow, University of Southern California

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recent Comments