Joseph Prezioso/AFP via Getty Images

Jessica A. Marino, University of California, Merced and Jennifer Hahn-Holbrook, University of California, Merced

The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

The big idea

One third of families who relied on formula to feed their babies during the COVID-19 pandemic were forced by severe infant formula shortages to resort to suboptimal feeding practices that can harm infant health, according to our research published in the journal Maternal and Child Nutrition.

Infant formula shortages left 70% of U.S. store shelves bare in May 2022, with 10 states reporting out-of-stock rates of 90% or greater.

As psychology researchers who study breastfeeding, this situation left us concerned for the safety of infant nutrition. With two colleagues who focus on public health, we conducted an online survey of over 300 infant caregivers in the U.S. to understand how many families had trouble obtaining infant formula and what they fed their babies when they did.

Considering the scope of the formula shortages, we were not surprised that 31% of the formula-feeding families we surveyed reported challenges obtaining infant formula, the most common being that it was sold out and they had to travel to more than one store.

But their babies still needed to eat. Being unable to get their hands on infant formula pushed caregivers to potentially unhealthy or even dangerous stopgaps. For example, 11% of the formula-feeding families surveyed said they practiced “formula-stretching” – diluting infant formula with extra water to make formula supplies last longer, which provides a baby with less nutrition in each bottle.

Furthermore, 10% of formula-feeding families reported substituting cereal for infant formula in bottles, 8% prepared smaller bottles and 6% skipped formula feedings for their infants, which all provide infants with less nutritious meals.

Exclusively breastfeeding families were insulated against these supply disruptions. Almost half of breastfeeding families surveyed reported that COVID-19 lockdowns actually allowed them time to increase their milk supply.

Why it matters

Our study suggests that the waves of formula shortages from 2020 to 2022 in the U.S. were more than just an inconvenience for parents. Instead, this study is the first to document that formula shortages likely had real and widespread adverse impacts on infant nutrition, given that a large proportion of parents surveyed resorted to feeding their baby in ways that can harm infant health.

For instance, studies have shown that adding extra water to “stretch” formula can result in infant malnutrition, growth and cognitive delays and even seizures and death in extreme cases. Adding cereal to bottles increases the risk of choking-related deaths and severe constipation. Moreover, feeding infants age-inappropriate foods can have lifelong consequences for cognitive development and growth, leading to a higher risk for chronic illnesses like obesity and cardiovascular disease.

Given that approximately 75% of infants in the U.S. are fed with infant formula in the first six months of life, formula shortages could put roughly 2.7 million babies each year at risk for suboptimal feeding practices.

Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

What’s next

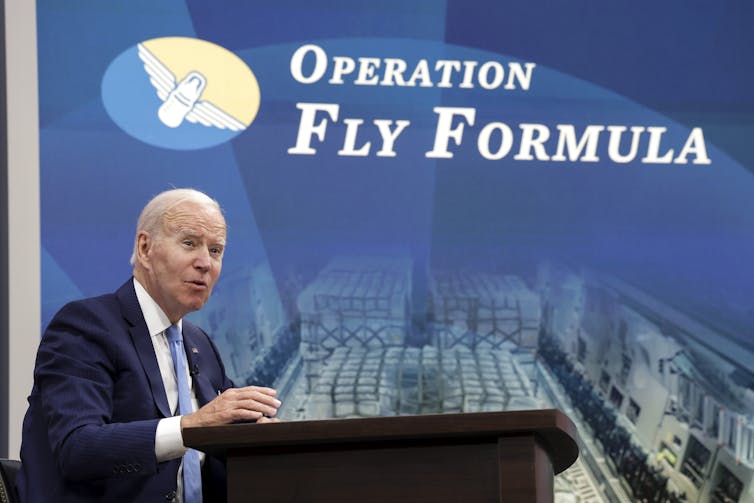

A perfect storm of formula recalls, ingredient shortages and shipping delays contributed to COVID-19-related formula shortages in the U.S. Although President Joe Biden’s administration has taken some steps to improve distribution infrastructure, the U.S. does not currently have infant nutrition disaster plans in place beyond common-sense recommendations for individuals.

Unfortunately, climate change will likely increase the risk of formula-supply disruptions over the next century because of the increased frequency of natural disasters.

The best way to protect infant nutrition from supply chain issues is to promote and support breastfeeding, which provides optimal infant nutrition and insulates infants from those disruptions. Since not all babies can be breastfed, though, governmental policies could help prevent and address acute formula shortages and ensure equitable formula access for all.![]()

Jessica A. Marino, Doctoral Student in Health Psychology, University of California, Merced and Jennifer Hahn-Holbrook, Assistant Professor of Psychology, University of California, Merced

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recent Comments