Michael Nagel, University of the Sunshine Coast

As someone who has spent most of his professional life studying how children develop, I’m often asked by parents (especially mums) why children (especially boys) are prone to pick up the nearest stick, pencil, soft toy or even banana and turn them into weapons?

Girls certainly do this too. But research – and parents’ experience – shows you’re more likely to find boys using various objects as swords, guns or grenades to attack one another.

While some parents worry this is too violent, these actions do not mean you are raising a burgeoning psychopath. Rather, they are significant components of healthy development.

Playful aggression

Role playing is a key part of children’s play, when they pretend to be someone or something else. They can do this on their own or with others.

When they do it with others it is called “sociodramatic play”. This type of play teaches children both verbal and social skills while they interact with others.

Play fighting is one form of sociodramatic play. It can include rough and tumble play, chasing one another around, superhero play, wrestling and mock fighting. Psychologists call this “playful aggression”.

This kind of play is not about hurting anybody. Rather, it provides opportunities for children to explore their world with a sense of empowerment and control (because they set the rules) and to build relationships as they negotiate the play.

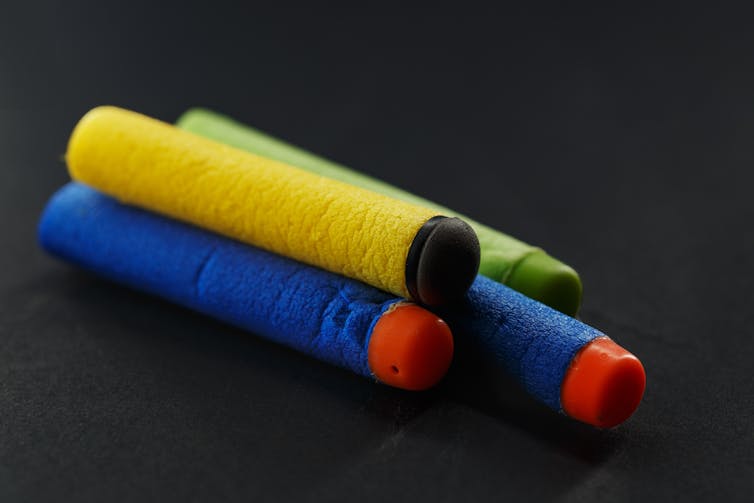

Mix Tape/ Shutterstock, CC BY

How does it work?

Imagine children are playing a battle with pillow forts and cardboard swords. This is not just a question of whose fort topples first. The game will require them to read facial expressions, express themselves and develop an awareness of power dynamics (or what researchers call “relationships hierarchies”).

Relationship hierarchies are complex, but focus on power and who is in charge. During episodes of playful aggression, this might mean taking control, giving in to someone else’s idea, or sharing power. These hierarchies allow children to make decisions about who they want to play with, who to avoid, or how to adapt their behaviour to create friendships.

So relationship hierarchies play an important role in emotional and social development. They teach children how to get along with one another, how to make and play within a rule structure and how to recognise the difference between playful and harmful behaviour.

For example, other children’s reactions during the game will teach them that yelling and jumping may be considered fun. But rough pushing or deliberately breaking rules – such as turning into a killer dragon when everyone else has agreed to be tigers – is not OK and will make your friends unhappy.

Why do we see this more in boys?

You might be wondering why such behaviours seem to be more evident in boys than girls. Research shows boys (on the whole) tend to be more physical in how they play.

Their play often focuses on themes related to power and dominance and playful aggression is the perfect way to experiment with these themes.

Theories about sex differences in social play extend across many research areas including psychology, neurobiology, evolutionary psychology and anthropology. Current theories link these differences to testosterone and differences in neurochemistry.

There is some evidence to suggest boys and girls are socialised differently in relation to being physical.

However, the degree of influence is contestable given sex differences in behaviour appear very early in life and in other mammals. Perhaps the socialisation process exacerbates nature – and as such, nature and nurture may be working in tandem.

The end result is still the same, with more boys than girls engaging in playful aggression.

When girls role play, it tends to focus on what researchers call “tend and befriend” or on people and nurturing. For example, games built around families or looking after pets.

But this is not to say girls can’t be aggressive. However, research suggests if girls fight it is usually done with words to hurt someone’s feelings and children are upset with each other. It is not done for fun.

Perhaps this is why playful aggression can be difficult for some mothers to understand and appreciate.

But there is no link between playful aggression in children and being aggressive as an adult.

8H/ Shutterstock, CC BY

Are you guys having fun?

For many parents, watching a group of boys mimic battles with sticks as guns or swords spells trouble. Odds are that they will tell the children to “stop before somebody gets hurt!” or “play something more gentle!”.

However, stopping this playful endeavour robs kids from engaging in perfectly natural, and developmentally desirable, behaviour.

Playful aggression is not serious aggression. If unsure, all parents and carers need do is ask whether everyone is having fun or not.![]()

Michael Nagel, Associate Professor – Child Development and Learning, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recent Comments