(Erinn Acland), CC BY-NC-ND

Erinn Acland, Université de Montréal and Joanna Peplak, University of California, Irvine

It may be surprising to hear that toddlers and preschoolers are the most physically aggressive age demographic. Luckily, they lack coordination and strength, making their attacks less dangerous than those of adults.

Overtly hostile behaviour tends to diminish with age — except for a minority of children who are at risk of later criminality. This makes childhood a critical time for steering those most in need of support away from difficult life paths.

Being blind to others’ negative emotions (anger, fear, sadness) is linked to callous-unemotional traits in childhood. These traits include a lack of guilt for harming others, a lack of empathy and generally being unemotional. A poor ability to detect others’ negative emotions is also uniquely tied to aggression.

If a child hurts someone, but can’t tell they’ve upset them, it means they won’t see the emotional consequences of their actions. The theory is this could make it easier for them to continue harming others.

But the caveat here is that not all aggression is equal.

Types of aggression

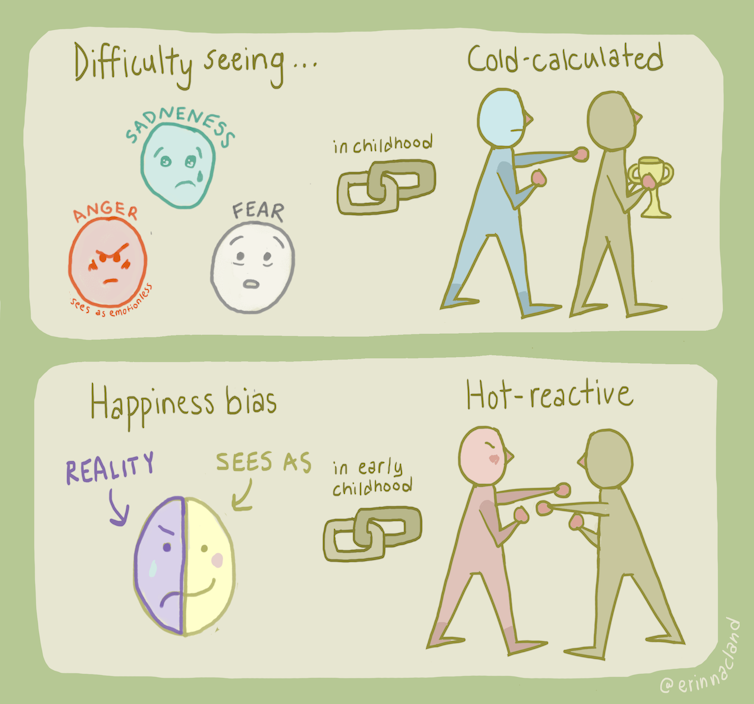

There are two types of aggression that represent differing emotional temperatures: cold-calculated and hot-reactive.

Cold-calculated aggression is when force is used to get a desired outcome. For example, a child hitting a peer to steal their candy without provocation. This type of “cold-hearted” aggression is tied to callous-unemotional traits.

Hot-reactive aggression involves harming others in response to provocation. Children who engage in reactive aggression tend to be more “hot-headed.” They have higher emotionality, unregulated anger and tend to assume hostile intent from others. If a reactive aggressor is bumped by a passerby, for example, they are more likely to assume it was on purpose and hit them in retaliation.

Although these types of aggression seem opposite, someone who is a cold-calculated aggressor in one situation can also be a hot-reactive aggressor in another. The type of aggression a child uses the most results in them being categorized as one or the other.

Until now, it was unclear how children’s abilities to read facial expressions might differ between these “hot” and “cold” types of aggression.

Difficulty recognizing emotions

Our recently published paper assessed two diverse samples of children — one of 300 children, the other of 374.

Children were shown pictures of faces that expressed differing intensities of sadness, anger, fear and happiness in a random order. They were asked to identify which emotion was expressed or whether no emotion was present. We considered caregivers’ education level, child age and child gender in our analyses.

(Cambridge University Press)

We found that blindness to others’ anger, fear and sadness was consistently related to using cold-calculated aggression. In other words, children who have difficulty understanding that they upset someone are more likely to harm others to get what they want.

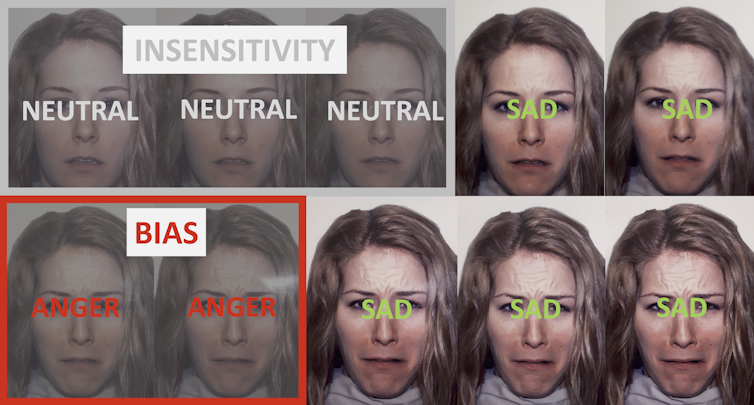

Interestingly, we found that the way children misrecognized angry expressions mattered. Cold-calculated aggression was tied to anger insensitivity. In other words, thinking angry expressions looked emotionless rather than another emotion.

This implies that children who harm others to get what they want aren’t as sensitive to social threats in their environment. This would allow them to remain calm in potentially dangerous situations.

Children who show more callous-unemotional traits and behavioural problems tend to be more fearless and less deterred by punishment, perhaps as a consequence of being more blind to threats.

We predicted that hot-reactive aggression would link to seeing anger in faces, regardless of whether the faces were actually angry. But surprisingly, that isn’t what we found.

Instead, thinking negative expressions looked happy was consistently linked to more hot-reactive aggression, but only in early childhood.

Youth who engage in more hot-reactive aggression have been reported to experience lower happiness on a daily basis, but are happier than their peers in response to positive events. So, perhaps young reactive aggressors are particularly sensitive to rewarding emotions. This may lead them to see happiness when it isn’t there.

Trouble figuring out the valence of an emotion (mistaking negative for positive emotions) could also be causing social blunders that result in conflict. Think about it: if you believe your friend is feeling happy, you have the green light to keep teasing or joking with them. But, if they are actually upset, this could stir up some serious friction.

This novel, unexpected link still needs to be teased apart in further research for us to understand what exactly is happening here.

(Erinn Acland)

What causes aggression in children?

Our study was correlational, meaning we can’t say for sure whether reduced emotion recognition causes aggression in children — only that these two things seem to be related.

However, a 2012 study does provide some support for a causal link. Researchers found that improving emotion recognition in callous-unemotional youth through training reduced behavioural problems and increased empathy for others’ feelings, when compared to treatment-as-usual. This means that when callous youth were helped to identify how others feel, some of their behavioural issues resolved.

In our study, children’s ability to recognize emotions explained five per cent or less of their aggression, depending on their age. So, targeting this social skill alone is likely not sufficient to resolve serious aggression.

Addressing systemic causes of violence (e.g., poverty) and investing in tailored early interventions that target multiple areas of child development and family well-being are necessary for promoting meaningful changes in children’s aggression.![]()

Erinn Acland, Postdoctoral Fellow, Developmental Psychology, Université de Montréal and Joanna Peplak, Postdoctoral Scholar, University of California, Irvine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recent Comments