(Shutterstock)

Written by Audrey-Ann Deneault, University of Calgary; Lorraine Reggin, University of Calgary; Penny Pexman, University of Calgary; Sheri Madigan, University of Calgary, and Susan Graham, University of Calgary

When children develop the ability to understand language, as well as speak and communicate, this helps them interact with others and learn about their world. Research shows that children’s early language skills have a long reach in affecting later life outcomes.

Children with better language skills have an easier time regulating their emotions and interacting with their peers, likely in part because they can more easily communicate their thoughts, feelings and ideas.

Children with better language skills are also more likely to be ready for, and succeed in school, and have better reading and writing skills. When they are older, they are more likely to be successful and fulfilled at work.

Given the clear importance of language skills for lifelong outcomes, it is critical to set children up early for language success. Parents, grandparents, caregivers as well as early learning and care programs can play vital roles in supporting children’s language skills. We present three ways to help build children’s emerging language skills.

(Bridget Coila/Flickr), CC BY-SA

1. Use language around children as often as possible

Talking to, around, and especially with children supports their language learning. This is the case for children of all economic and cultural backgrounds.

Both the quantity and the quality of what caregivers say matter for children’s language learning.

Our research shows that children who hear more words and sentences have more words in their vocabulary and stronger language skills. So, as much as possible, talk with your children. Even when they can’t speak, children are still absorbing and learning from the language they hear around them.

(Pexels/Keira Burton)

Pretend you are a commentator, talking out loud about what you are doing, why you are doing it, and what’s happening in the child’s environment. For example, when sitting at a park with your baby or preschooler, you might say:

“Look at the green tree. It’s a maple tree. How many trees do we see? That tree looks different from the tree by the bench…..”

It is not just the number of words that children hear that is important — the quality of the language children hear also matters.

That means it is important to use a variety of words and sentence structures when talking to children. For example, instead of just pointing to a dog and labeling it, you can describe the fur colour of the dog, talk about what the dog is doing, and ask questions about the dog.

For example:

“Look at the dog. The dog is so big and fluffy and has such long legs. The dog is running towards the ball. That ball sure bounces. I hope the dog can catch it.”

Caregivers can also ask questions starting with words like “who, what, when, where, and why” to encourage children to provide a more complex response. This gives them the opportunity to use new words and sentence structures in their own speech.

Open-ended statements are also great to encourage language growth. You can use statements like: Tell me more, is that so, and then what happened…? Try to wait at least five to ten seconds to give your child time to respond.

(Shutterstock)

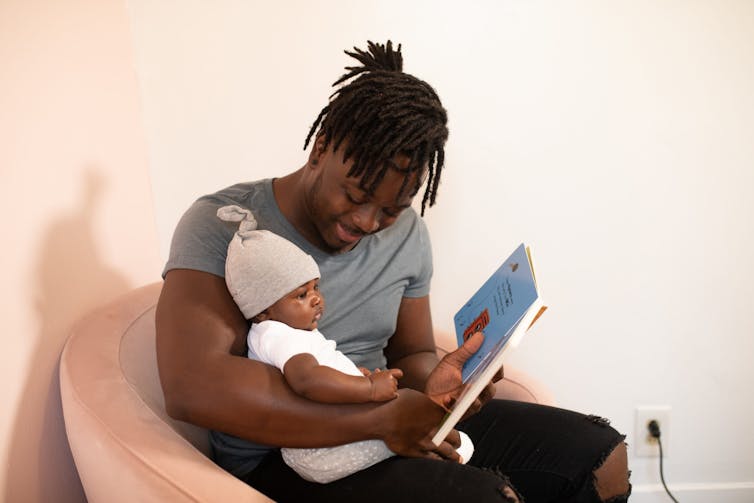

2. Read books with children daily

Shared book reading provides another great opportunity for language learning. Book reading exposes children to new words that are less commonly used in everyday speech as well as a variety of sentence structures. Books are a great way to expose children to high quality language as well as create a unique bonding experience.

Reading together also helps children focus and pay attention for longer periods of time, which helps them learn and sets them up for success in school.

Caregivers can try to make reading with children part of their everyday routine. How you read can help improve the child’s ability to learn new words. Describe pictures, give a definition for new words, ask questions, and incorporate music. Stories provide an opportunity to make links with your child’s experiences. Even when children are still young, invite them to turn the pages of the book and ask them what they think might happen next.

(Pexels/Nappy)

3. Engage in ‘serve and return’ interactions

Language skills can be developed through everyday interactions between caregivers and children. Sensitive caregivers notice vocalizations, cries, facial expressions, and other clues signaling that children need help, comfort or reassurance.

Sensitive interactions are often called “serve and return” interactions because they are like a game of tennis. The child “serves” a cue by pointing to something, asking a question, or saying something, and the caregiver needs to “return” the serve by repeating, answering or commenting.

While parents can be sensitive when speaking with their child, they can also show sensitivity by comforting a child who is sad or hurt. Our research shows that when caregivers are sensitive to their child’s needs and engage in serve and return interactions, children develop better language skills.

Even young infants benefit from serve-and-return interactions. For instance, ask your infant a question, and give them some time to answer! When they do, through uttering a sound like “da”, repeat it again, and then elaborate by saying “dada” and connect it to a reference point (like “daddy”) to encourage more language use and understanding. That way, we can support children’s inherent drive to connect and communicate with us.

Children begin learning language as very young babies and continue to develop their language abilities throughout childhood. Caregivers can help develop and enhance this important skill in everyday life by talking, singing, reading and tuning into them!![]()

Audrey-Ann Deneault, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Department of Psychology, University of Calgary; Lorraine Reggin, PhD student, Cognitive Psychology, University of Calgary; Penny Pexman, Professor of Psychology, University of Calgary; Sheri Madigan, Professor, Canada Research Chair in Determinants of Child Development, Owerko Centre at the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute, University of Calgary, and Susan Graham, Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recent Comments