Lauren Breen, Curtin University

Death and grief are not easy to talk about. Talking to children about these can be harder still.

Our instinct to protect children from harsh realities means we might avoid these topics altogether.

But, as we discovered in our recently published research, bereaved children have lots of questions about death and grief.

Child grief is common

Children experience grief much more commonly than most of us think. One study in Scotland found that, by the age of ten, 62% of children report having been bereaved by the death of a family member, usually a parent, sibling, grandparent or other close person.

Research in the United Kingdom finds about one in 20 teenagers will have experienced the death of their parent. By the age of 25, up to 8% of children and young people in a US study had lost a sibling.

Shutterstock

What we did

We analysed questions about death and grief from more than 200 children aged five to 12 years. They had experienced the death of a parent, sibling or other family member (such as an uncle or grandmother) in the past four months to five years.

Causes of death included cancer, car crashes, heart attacks, suicide, workplace accidents, substance use and childhood illnesses.

Children had submitted their questions while on a Lionheart Camp for Kids, a two-day camp to support grieving children, teenagers and families in Western Australia.

What we found

Our study, published in the Journal of Child and Family Studies, found many of the children’s questions were sophisticated.

They revealed curiosities about various biological, emotional and existential concepts, demonstrating complex and multi-faceted considerations of their loved one’s death and its impact on their lives.

Many questions reflected egocentric thinking typical of children (thinking that relates to themselves), such as thinking they caused the death.

We grouped their questions into five topics.

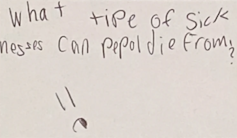

1. Why and how people die

Journal of Child and Family Studies, CC BY-SA

The most common question was about causes and processes of death.

These questions captured children’s curiosities and concerns regarding why and how people die.

For instance, they wanted to know how and why heart attacks, cancer, suicide and substance use happen. Some children wanted to know how and when they’d die.

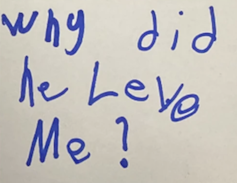

2. Managing grief

Journal of Child and Family Studies, CC BY-SA

These questions reflected children’s efforts to make sense of death and their subsequent social and emotional experiences.

They tried to understand their emotions and responses such as changes in sleeping patterns and physical sensations.

They also asked questions about how they could gain support from peers and teachers.

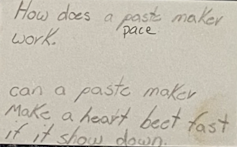

3. Human intervention

Journal of Child and Family Studies, CC BY-SA

These questions were about specific technologies such as pacemakers, and treatments such as medications, involved in preventing death and helping people who are dying.

Some children wanted to know how to prevent future deaths in their family.

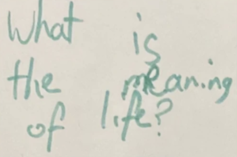

4. The meaning of life and death

Journal of Child and Family Studies, CC BY-SA

These questions captured the children’s existential concerns about life’s purpose and why people die.

These included questions about why some people can die so young, but others live for many years.

5. After death

Journal of Child and Family Studies, CC BY-SA

The final question type included ones relating to a person once they had died.

Many questions were about after-death destinations, such as heaven, and the possibility of reincarnation.

What now?

Children are aware adults are reluctant to discuss death with them. But shielding them from details could add to their distress and worry.

Our research shows children who have experienced the death of a close person want to know how to cope with difficult emotions and need support, validation and reassurance.

They need adults around them to encourage them to ask questions, then for those adults to listen and answer. And adults should try to find opportunities to start a conversation with children, bereaved or not, about death and grief.

Shelly Skinner (Lionheart Camp for Kids and Perth Children’s Hospital) and Lisa Cuddeford (Perth Children’s Hospital) co-authored this article.

If this article raises issues for you or someone you know, call Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800. Online resources are also available on how best to support a child experiencing death and grief.![]()

Lauren Breen, Professor of Psychology, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recent Comments